Tick-borne Diseases: A Threat to Livestock

Other

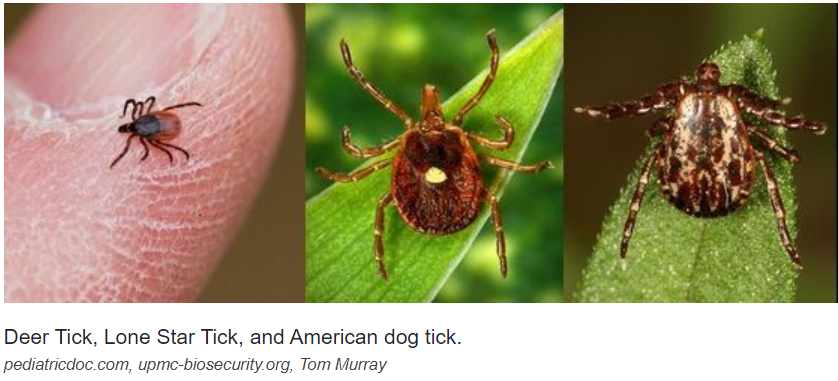

With over 900 species of ticks in the world (Horak et al., 2002) it is no surprise that tick borne diseases have become a significant health concern for humans and livestock alike. Ticks are classified into two categories: hard and soft, and they have four stages of their lifecycle, egg, larvae, nymph and adult. All ticks feed on blood during some or all stages. Ticks have remarkably long lives with many surviving for one or more years without feeding. The American dog tick (or wood tick), deer tick, Lone Star tick, brown dog tick, and Asian longhorn tick are all common hard ticks found in the Shenandoah Valley area.

What diseases do these pesky parasitic arachnids transmit to livestock? There are a number of tick-borne diseases, but we will focus on the Shenandoah Valley area in this discussion. Let’s start with two of the most prevelant production diseases in cattle:

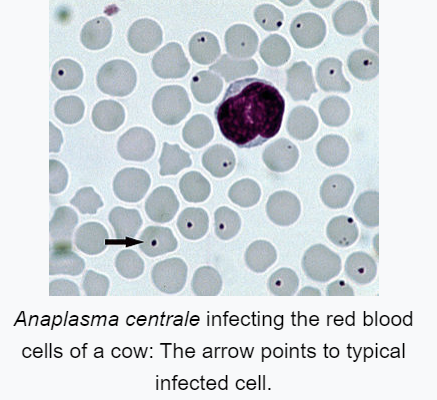

- The black-legged tick is the most common vector of anaplasmosis, a bacterial disease that can be found within the red blood cell, which causes death and rupture of the infected cells. There is a correlation between the age of cattle and the severity of the disease. This disease commonly infects calves, but they typically don’t show symptoms of infection. Older cattle that have never been exposed to anaplasmosis are more likely to succumb to the infection. Common symptoms are weakness, anemia, and yellowing of the mucus membranes. Abortion has been noted as well. Goats may be slightly more sensitive than sheep to anaplasmosis infection. Anaplasmosis in horses can result in weakness, laminitis, and fever, A veterinarian can easily diagnose anaplasmosis utilizing a blood smear and is commonly treated with tetracyclines. Like all blood-borne diseases, this disease can also be spread by other biting insects and contaminated equipment.

- The Asian longhorn tick (ALHT) is a vector for the disease, Theileria orientalis. This protozoal disease infects the red and white blood cells and exhibits similar symptoms as anaplasmosis. Typical clinical signs are yellowing of the mucus membranes, anemia, weakness & death. This is an emerging disease and has proven to be economically significant due to deaths and production losses. This disease affects all age groups, and if animals recover they commonly become carriers. The ALHT has been found predominantly on the east coast but is spreading west with animal movements. The female ALHT can lay between 400-1200 eggs and she reproduces asexually, meaning she makes exact genetic replicas of herself. There have only been female ticks identified in the US to date. Since this tick reproduces so effectively, it is not uncommon to see an extremely high density of these ticks. Most producers note large numbers of ticks on their cattle in the brisket, between the shoulders and flanks, and near the vulva and rectum. Sheep and goats are showing some sensitivity to this disease. Field reports are indicative of infection, though it affects small ruminants less than cattle. As an emerging disease, data is regularly collected, and much is being learned from that information. A majority of the research is being conducted in Virginia. Currently, there is no treatment available aside from supportive care.

The OneHealth initiative is a mindset that includes humans, animals, and the environment. It allows us to be more mindful of diseases and how all three components are affected, which leads us to the next diseases of concern.

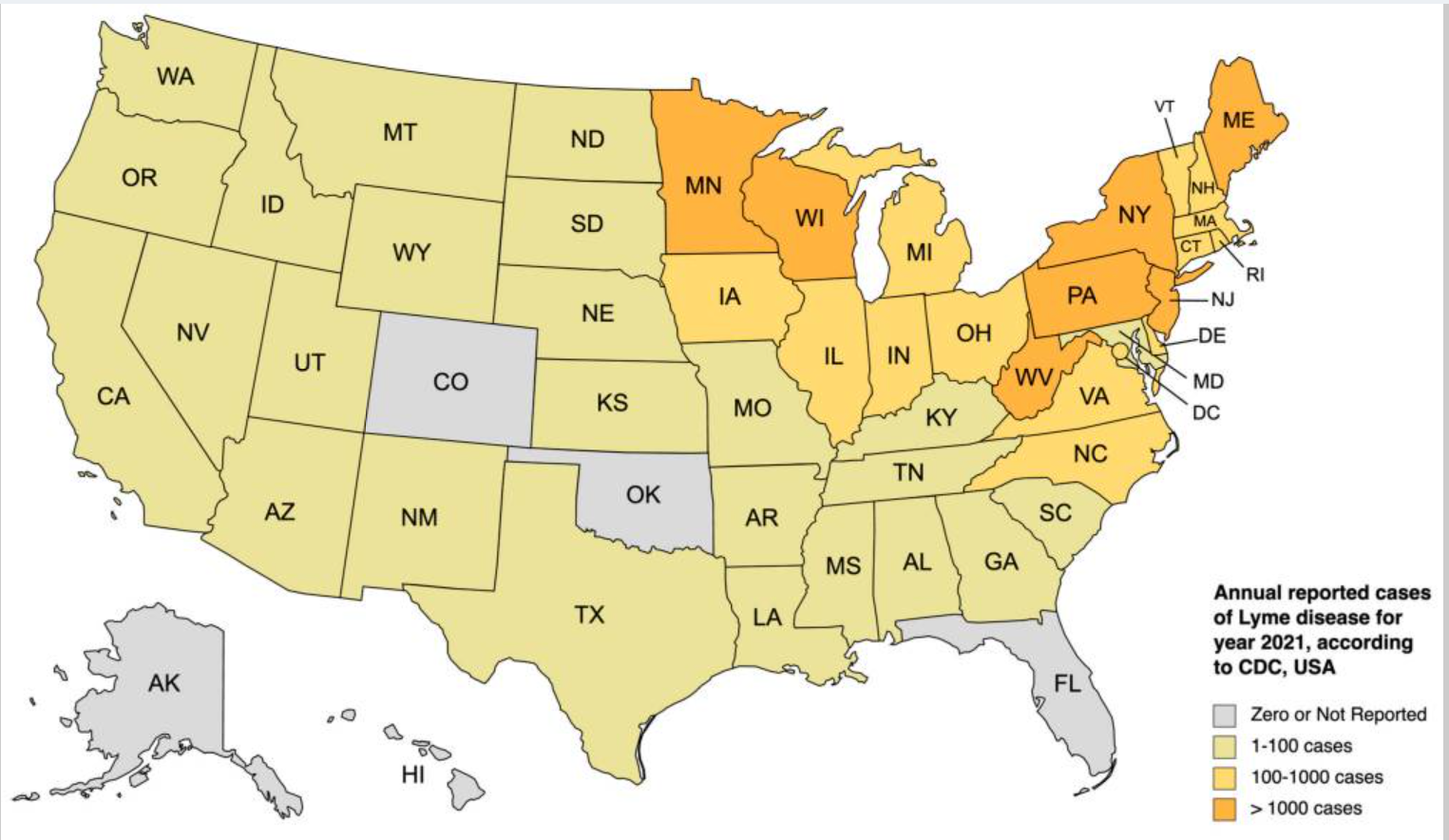

- The most common tick-borne disease in humans in the USA is Lyme disease or Borreliosis, an infection caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorfei. Over 1000 cases of Lyme disease were reported in humans in 2021(NIH.gov) in both Virginia and West Virginia. In theory, infections of livestock with Lyme disease are prevelent too, but this is not a disease that we regularly are concerned about affecting cattle, sheep, goats, and swine. There have been reports of infection in horses that tested positive after exhibiting neurologic signs and uveitis, inflammation of the eye. Also, our canine companions can develop the infection and, as a result of a renal syndrome known as Lyme nephritis, it’s sometimes fatal. Detection of Lyme disease in dogs has become common within the last 10 years. Lyme disease is commonly transmitted by the deer tick, and treatment is available.

- The lone star tick can be a vector for diseases such as Ehrlichia, tularemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and the alpha-gal allergy. These diseases are all of concern but are diagnosed less frequently in livestock. This tick, which is easy to distinguish, can cause a red meat allergy in humans who are affected.

The discussion on ticks and tick-borne diseases is limited on this platform. However, one tick-borne disease that the USDA is trying to prevent from entering the US should be discussed here.

- Babesia results in a disease commonly called Texas Cattle Fever or “redwater” disease, which is found in Mexico. The tick family Boophilus is a common vector for this parasitic protozoan. The USDA manages a permanent quarantine zone in Texas to prevent the spread of this tick and, therefore, the disease. Practices such as dipping cattle in vats or using injectable medications every 14 days are used to control the ticks' spread. Horses are commonly infested with this tick and follow treatment protocols as well.

Tick-borne diseases have similar signs and symptoms. “If you are raising livestock, then you must stay informed about the specific tick-borne diseases prevalent in your region and be aware of any emerging threats. Regular surveillance of tick populations and disease prevalence can provide valuable insights for preventive planning.”( Tick-Borne Diseases in Cattle - bdvets) Talk to your attending veterinarian to establish tick control and treatment strategies specific to your location and operation. Collaboration between farmers, veterinarians, and researchers is vital to combat tick-borne diseases effectively. Public health monitors tick borne diseases in humans through reporting of confirmed cases. They also monitor tick types and the pathogens present in ticks that are collected. Tick-borne diseases are a OneHealth concern. If you find an attached tick, please contact your physician for evaluation.

For more information on tick-borne diseases, please contact your practicing or regulatory veterinarian, local extension agent, or local health department.

Author:

Dr. Vanessa Harper

References:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/theileria-orientalis-ikeda-notice.pdf

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28598270/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9210854/

https://www.merckvetmanual.com

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2017.00298/full

https://www.cdc.gov/alpha-gal-syndrome/about/index.html

https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/ticks/tick-identification/

https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/11/17/1063352/new-tick-borne-disease-killing-cattle-in-us/

https://bdvets.com/blog/tick-borne-diseases-in-cattle#_Epidemiology_of_Tick-Borne

https://bdvets.com/blog/tick-borne-diseases-in-cattle#_Anaplasmosis_-_The

https://oeps.wv.gov/arboviral/Pages/tbd.aspx

Horak IG, Camicas JL, Keirans JE. The Argasidae, Ixodidae and Nuttalliellidae (Acari: Ixodida): a world list of valid tick names. Exp Appl Acarol. 2002;28:27–54. doi: 10.1023/A:1025381712339.